Deepfake Democracy and the Liar’s Dividend

When AI Can Fake a President, What Happens to the Truth?

In May 2025, Argentina’s capital was rocked by a new kind of election interference: an AI-generated video, circulated widely on social media, appeared to show a prominent political figure endorsing a rival candidate. Released during the pre-election silence period, the video was quickly denounced as fake, but not before reaching millions and potentially influencing the outcome. This is a vivid example of how generative AI and deepfakes can rapidly reshuffle a political landscape.

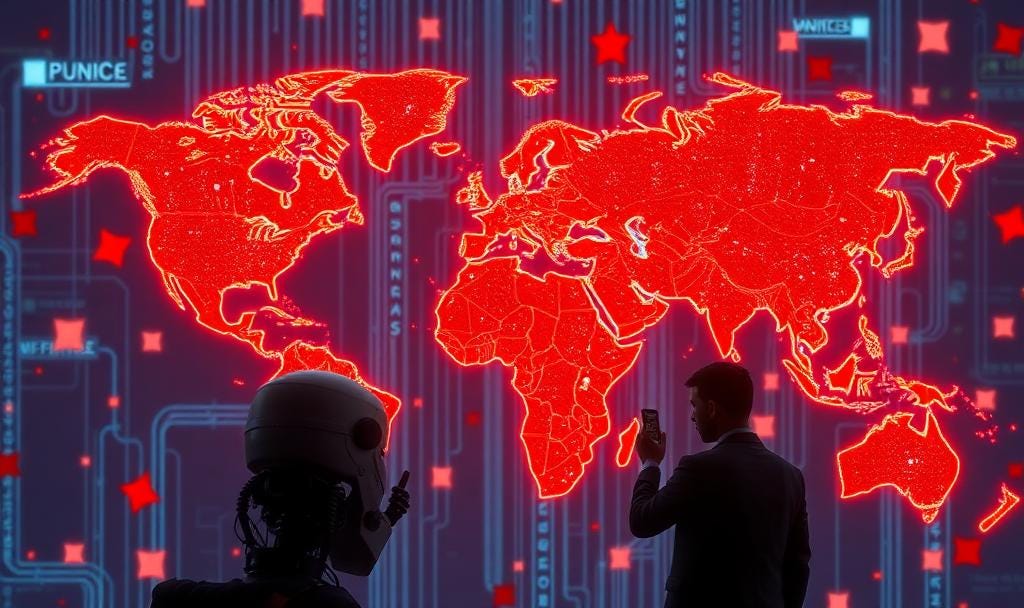

Argentina’s recent experience is part of a global wave. In their 2023 presidential race, both major campaigns in Argentina weaponized AI: Javier Milei’s team distributed fabricated images of his opponent Sergio Massa dressed as a communist general, while Massa’s supporters used AI to create images of Milei as a zombie or pirate. The technology is now so accessible that anyone with a smartphone and a few minutes can create convincing fake photos, videos, or audio, making it nearly impossible to distinguish real from fake, even for experts. The goal? To go viral, inflame passions, and blur the line between truth and fiction.

This phenomenon is certainly not limited to Argentina. Around the world, deepfakes and AI-driven disinformation have already muddied elections in places like Slovakia, where a faked audio tape of a candidate discussing vote rigging spread just days before the polls, and Moldova, where a deepfake video of the president endorsing a pro-Russian party aimed to erode trust in the electoral process. In Bangladesh and India, deepfakes targeting politicians have gone viral, particularly in communities with lower digital literacy. This amplifies risks in countries with lower digital capacity — and little recourse for victims or fact-checkers.

Even in the United States, where regulatory efforts are underway and public awareness is higher, the deepfake threat is growing. The 2024 election cycle saw the first widespread use of AI-generated robocalls, fake news sites, and manipulated videos targeting candidates and voters alike. In one case, a robocall using Joe Biden’s voice urged New Hampshire Democrats to stay home—a clear-cut attempt at voter suppression. The U.S. Federal Election Commission and Congress are now considering new rules to regulate AI-generated political ads, but the pace of campaign innovation continues to outstrip the speed of political regulation.

The real danger is not just that a single fake video might fool voters, but that the sheer volume and sophistication of AI-generated content could eventually make people doubt everything they see and hear (a “hall of mirrors” in intelligence speak). This so-called “Liar’s Dividend” allows candidates and their supporters to dismiss real evidence as fake, undermining accountability and weakening democratic institutions everywhere. Watermarks, fact-checking networks, and disclosure rules are being tested, but none have scaled to meet the moment. As deepfakes become more convincing and common, the ultimate challenge may not be technological, but philosophical: defending the very idea of truth in the public square.